Treasure Island has been a place of entertainment and performance, from its establishment as the site of the Golden Gate International Exposition (1939-1940) to its years as Naval Station Treasure Island (1942-1997) and beyond. During the fair, millions visited to see the spectacular architecture and creative, commercial and technological marvels on display.

Visitors enjoyed an extraordinary variety of performances, including traditional, classical, and contemporary music, as well as theater and dance spanning cultures and centuries. Music and art from countries around the Pacific mirrored the fair's theme of “Pacific Unity." Parades and pageants provided entertaining diversions.

But war ravaged Europe and Asia during the years of the fair, and in 1942, Treasure Island became a Navy base. After the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor in late 1941, “Pacific Unity" seemed ironic, if not naïve. But music and entertainment continued to provide diversions for sailors on Treasure Island.

After base closure in 1997, the Treasure Island Music Festival brought the newest acts to thousands of attendees. This rich history of diverse entertainment, begun at the GGIE, continues as Treasure Island evolves into the 21st century.

As Sounds Go By

Performing Arts at the GGIE, 1939-40

Cavalcade of the

Golden West

The Cavalcade of the Golden West (1939) was a breakneck race through the history of the American West, with broad humor, tear-jerking melodrama, and lots of action.

The show was boisterous and larger-than-life. Its script was melodramatic, even by the standards of the 1930s (see an excerpt from the script below).

It was enthusiastically patriotic and wholesome; it was also very old-fashioned. Its view of American history was one-sided and over-simplified. Native Americans roles, portrayed by white performers, were broad stereotypes rather than developed characters.

Adventure and patriotism in the Cavalcade of the Golden West. 2021.001.001P.

But the spectacle was very impressive: “covered wagons, steam locomotives, soldiers on horseback and a [cattle] stampede” all happened onstage! There were gunfights and reenactments of famous speeches and events. 300 actors (and 200 animals) put on three shows a day on a gigantic stage.

The production included antique cars, stagecoaches, wagons and TWO running locomotives. Each cast member played multiple roles, requiring frantic costume changes backstage.

The show came back in 1940 as America! Cavalcade of a Nation, telling similar stories on a national scale.

Sheet music for the Cavalcade of the Golden West’s theme song. 2013.13.5.

Typed script for Cavalcade of the Golden West. 2013.13.1

Lines were read by an actor in a booth and amplified through loudspeakers. Actors onstage pantomimed the story.

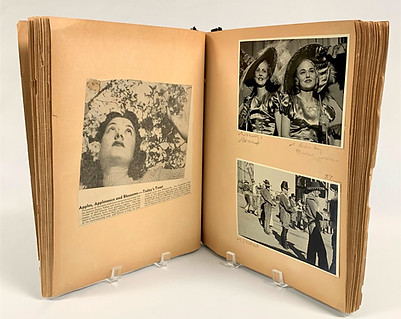

The Treasure Island Museum recently received a scrapbook of photographs taken backstage at the Cavalcade.

Scrapbook from the Cavalcade of the Golden West: 2021.001.001.

Backstage at the Cavalcade of the Golden West. 2021.001.001H.

These candid photos show actors relaxing backstage. Clearly, the cast enjoyed the Cavalcade just as much as the audience.

Spanish conquistadors onstage at the Cavalcade of the Golden West. 2021.001.001N.

The patriotic finale of the Cavalcade of the Golden West. Color slide by Paul Jacob, courtesy of Paul Totah.

Nostalgia at the GGIE

The GGIE was designed to appeal to the entire family, young children as well as parents and grandparents. Jazz, swing and other hot new music filled the air, but older visitors found plenty to enjoy as well.

The senior citizens of 1940 had been young adults in the Gay Nineties, and still enjoyed “retro” entertainment.

A segment of the Cavalcade of the Golden West was set just before (and during!) the San Francisco disaster of 1906.

It featured old-fashioned “high wheel” bicycles, early automobiles and “Gibson Girl” hairstyles.

The ASCAP concert included barbershop quartets and other nostalgic music from visitors’ youths.

Listen to a barber-shop standard Sweet Adeline, sung by the Haydn Quartet in 1904.

Pianist Mildred Fouts gets ready to perform in vintage costume at the Fair Fiesta. The Bancroft Library.

Curtain call at the Cavalcade of the Golden West. 2021.001.001J.

Children’s Entertainment

The entire family was welcome at the GGIE, which included plenty of attractions just for kids. There were puppet shows, including the Salici family’s famous Italian marionettes. The Cavalcade of the Golden West was considered to be the best “family show” at the fair.

Walt Disney visits the Golden Gate International Exposition. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

A new Disney cartoon premiered at the GGIE: Mickey’s Surprise Party. Disney had already released many cartoons with Mickey and Minnie Mouse, but this was the first appearance of their modern designs.

It was also the first time that a Disney cartoon advertised a commercial product: Nabisco cookies, crackers and dog biscuits (for Pluto).

Watch Mickey's Surprise Party (1939) here!

The whole family came to the GGIE, but certain shows were for adults only. There were sophisticated nightclub revues, like the Folies Bergère, and sideshows with nude “artist’s models.”

The most notorious show on the “Gayway” was Sally Rand’s Western-themed Nude Ranch. Rand, a burlesque legend who became famous performing at world’s fairs in the 1930s, pioneered the legendary “Fan Dance” and made a brief break into Hollywood films.

Rand didn’t perform at the GGIE herself. At the time, she owned the Music Box Theater on O’Farrell Street in San Francisco; this beautiful venue is still there today, as The Great American Music Hall.

Watch Sally Rand’s performance of the “Fan Dance” in the film Bolero, 1934.

Sally Rand leaning against the new Luscomb airplane in front of the Nude Ranch. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Interior of Folies Bergère program. 2018.15.3.

Meanwhile, back at the (Nude) Ranch…

ASCAP Concert

The fair concluded with a major music festival, courtesy of The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP).

A classical concert in the afternoon featured the SF Symphony and pieces by William Grant Still, an important Black American composer.

A remarkable concert followed that evening, with performances by dozens of popular American composers and performers. Tens of thousands of people crowded the venue.

Highlights included Judy Garland, Hoagy Carmichael, W. C. Handy, and dozens more stars of stage and screen. The concert was recorded. It was never broadcast, but was remembered as a “racially inclusive, upbeat, celebratory music party.”

Listen to a 1939 recording of Somewhere over the Rainbow sung by Judy Garland.

An outdoor band concert. Color slide by Paul Jacob, courtesy of Paul Totah.

Judy Garland in 1939. The Wizard of Oz premiered in 1939, the year before the memorable ASCAP concert concluded the GGIE.

Big Band, Jazz, and Swing

Prior to the 1930s, world’s fairs emphasized industry and technology over entertainment. Musical performances were mostly serious, meant to educate and “improve” listeners.

Treasure Island was a different kind of fair; there was plenty of serious music, but also fashionable, fun modern music.

Just a few days after the sudden closure of the Swing Mikado, jazz fans were treated to an extended sold-out residency by “the King of Swing,” Benny Goodman. Bing Crosby, Count Basie and Duke Ellington also performed to huge crowds.

During the fair, Treasure Island hosted regular dances in the evenings, often several on the same night.

Benny Goodman’s band onstage at the GGIE. Color slide by Paul Jacob, courtesy of Paul Totah.

Watch a home movie of Benny Goodman performing at the GGIE by clicking the image above (1 minute in).

W. C. Handy

Father of the Blues

Watch W. C. Handy perform St. Louis Blues on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1949!

William Handy, “the Father of the Blues,” was born in Alabama in 1873. As a young man, he performed at the world’s fair in Chicago in 1893. His performance of St. Louis Blues at the GGIE was a highlight of the ASCAP concert that concluded the fair in 1940.

Handy didn’t invent the blues, but he helped popularize Black folk music beyond the South. His compositions and recordings were extremely important in the development of jazz and blues.

Years later, Handy recalled his trip to Treasure Island fondly, and remembered the ASCAP concerts as “the greatest program of all-American music ever staged.”

W. C. Handy

Library of Congress.

W. C. Handy

Wikipedia.

World Music at the GGIE

At the fair, American audiences enjoyed authentic music from around the Pacific Rim. Performers from Central and South America, Asia and Polynesia visited Treasure Island.

Established ethnic communities in California sent performers to the fair. Classical Chinese opera was presented by performers from San Francisco’s dynamic Chinatown, and a traditional Armenian band came from Fresno.

There were marimba bands from El Salvador and Guatemala, musical groups from Hawaii, and an orchestra from Brazil. Indonesian gamelan music performed at the fair made a deep impact on Lou Harrison and other California composers.

Listen to music by composer Lou Harrison, inspired by Indonesian music at the GGIE.

“Fiesta Serenaders” at the GGIE including Manuel Castaneda, Frances Flores, Juanita Ayala, Sabino Rivas, Anita Romano and Miguel Oroseo. The Bancroft Library

Chinese Village with opera troupe, Golden Gate International Exposition. The Bancroft Library.

An Armenian Band from Fresno. The performers are Garabed Gejeian, Oscar Kadorkian and Robert Bedrosian. San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Swing Mikado

The 1930s were a time of exciting new types of music and dance, and classic shows were updated in new fashions to appeal to modern audiences.

Swing Mikado, originally a production of the WPA’s Federal Theater Project, adapted Gilbert and Sullivan’s familiar show with contemporary “swing” music and an all-Black cast.

The story was transplanted from feudal Japan to a make-believe island in the South Pacific.

Political criticisms of progressive New Deal programs closed the show after only two weeks on Treasure Island.

The show premiered in Chicago and New York City before moving to Treasure Island in 1939.

It then enjoyed great success at the Geary Theater in San Francisco, followed by a tour of Western states.

Poster advertising the Swing Mikado on Treasure Island. Library of Congress.

Cast of The Swing Mikado in Chicago, 1938. Wikipedia.

Making A Splash

Billy Rose’s Aquacade

After its success at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, impressario Billy Rose’s popular Aquacade show moved out West for 1940. It was a lavish spectacle of synchronized swimming, elaborate water ballets and thrilling high dives.

Visitors remembered its “schmaltzy music, slapstick comedy and pretty girls.” The Aquacade starred Johnny Weissmuller (the famous movie Tarzan), among many famous swimmers. Esther Williams, a young champion athlete introduced in the show, went on to be a movie star as well.

Like many shows at the GGIE, Aquacade had an elaborate, patriotic finale. The show was a huge success, both financially and with the public.

Aquacade program front cover. 2015.3.11.

Billy Rose’s Aquacade. Color slide by Paul Jacob, courtesy of Paul Totah.

The patriotic finale of Billy Rose’s Aquacade.

Acknowledgements

This exhibit was curated and developed in the summer and fall of 2021 by Joe Angiulo, as a curatorial internship via the Museum Studies graduate program at San Francisco State University.

On display are objects and documents from the collection of the Treasure Island Museum, as well as material graciously provided by the San Francisco Public Library and the Bancroft Library.

Thanks to the Museum’s Board of Directors for their expertise, assistance and encouragement; and particularly to Melanie Garduno (Collections Manager) and Annamarie Morel (Museum Manager).